Grenon’s paintings on glass conveyed folk-art vigor and psychological vitality: a stark gaze back at the viewer’s gaze.

Oregon Arts Watch | February 13, 2022 | Bob Hicks | Culture, Visual Art

Gregory Grenon, a leading figure in Portland’s contemporary art circles for close to 40 years, died on Feb. 6, 2022, at age 73. He and his wife, the artist Mary Josephson, had recently returned from a month-long stay in Italy.

Grenon was a Midwesterner who came into his own after moving to the Pacific Northwest, making his mark in Portland and nationally with rough-hewn, deeply color-saturated oil-on-glass paintings that suggest both folk-art vigor and psychological portraiture. They are mostly paintings of women, often quite large, and usually painted on the reverse sides of the glass, a process that can give them a kind of elusive shine. They are in many public and private collections and can be seen in prominent public spaces around Portland, including Keller Auditorium.

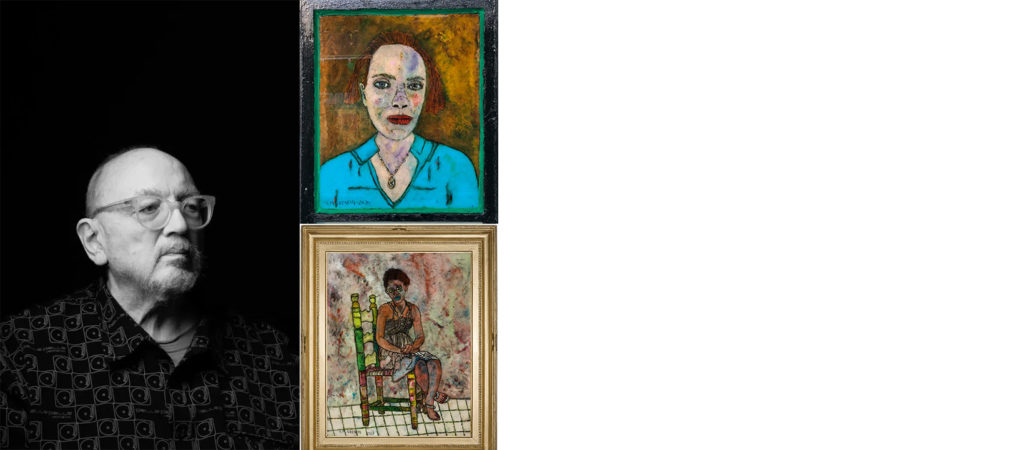

Gregory Grenon in 2020. Photo: K.B. Dixon

Grenon has been represented in Portland since 1995 by Russo Lee Gallery and its predecessor, Laura Russo Gallery. “Gregory grew up in Detroit, Michigan where he studied at the Center for Creative Studies and began making art in Detroit’s Cass Corridor, a thriving center of the arts in the 1960s and ’70s,” the gallery said in a statement announcing his death. “After a stint in Chicago, where he furthered his printmaking skills at Landfall Press, he moved to the Pacific Northwest in the late 1970s.”

Gregory Grenon, “Louisville,” 2020, oil on glass, 20.75 x 24.25 inches. Courtesy of Russo Lee Gallery.

Gregory Grenon, “Making Pictures That Are in My Head,” 2020, oil on glass, 37.5 x 37.5 inches. Courtesy of Russo Lee Gallery.

It’s hard to overstate the impact Grenon’s paintings had on Portland’s cultural scene in the late 20th and early 21st centuries. His work was known and instantly recognized not just inside the visual arts circle but also by a broad swath of the city’s citizens. There was something both immediate and subliminal about them, simple and complex, endearing and disturbing. Like the simpler drawings of the cartoon artist Roz Chast, they were both messy and inspired, speaking not so much of ideals, which they had a habit of subtly deflating, but of actual people in actual situations, with actual hopes and fears and dark experiences that they were dealing with in their everyday lives. Cartoonish? Only on the surface: bold lines not quite concealing the emotional turmoil below. And, more often than not, something more than that: a defiance, a stark gaze back at the viewer’s gaze, a determination to be taken seriously and to prevail. In painting after painting, these figures convey strength and character – not as “role models,” but as people, buffeted yet carrying on.

Gregory Grenon, “I Won’t Be Wronged”, 2015, reverse oil on glass, 47.5 x 38.5 inches. Courtesy of Russo Lee Gallery.

Carrying on, and knowing how and when to do it, seemed crucial to Grenon’s approach to life and art. “This is it, viewers,” Grenon wrote in his artist’s statement for an online exhibition in April and May of 2020. “What I have here is an important outlet for the resolution of inner tensions. I encourage young painters and those who have not painted, to work in private; to work at home until their individual styles have set beyond premature influence. Think and wonder how much you can improve the strange little drawings you have been making for years if you had paint and brushes.”

Gregor Grenon, “Maybe I Shouldn’t Care,” 2018, oil on curved oval glass, 16.75 x 22.875 inches. Courtesy Russo Lee Gallery.

In a 2016 ArtsWatch review, longtime arts writer Paul Sutinen noted that Grenon’s painted frames are not just decorative, but are crucial integrated aspects of his paintings. And, taking a long view, he remarked on how much had stayed the same and how much had changed over the years in Grenon’s art: “Writing about Grenon’s work 30 years ago, I said, ‘But his main strength for me is color, whether it is brilliant or grayed. Traveling over a cheek or under an eyebrow in one of these faces you can find the most surprising juxtapositions of color. There are oceans of subtlety within the borders of these faces. The face is the constant and everything else changes.’ He’s still at it. I don’t think he’s stuck in his motif, but utilizes it the way Morandi explored the simple still life or Rothko explored the possibilities of color and nuanced edges of floating rectangles for decades.”

Indeed, throughout his life and career Grenon paid attention to the vital tug between action and reflection, each necessary to push his art forward. Photographer and writer K.B. Dixon, while working on Face to Face, his 2015 book of portraits of 32 prominent Oregon artists, shot a series of photos of Grenon in the artist’s studio. “It is the artist at work assessing the progress of a new piece,” Dixon said a few days ago of the photo below. “I always liked it—it captured an important moment, a moment of creative contemplation.”